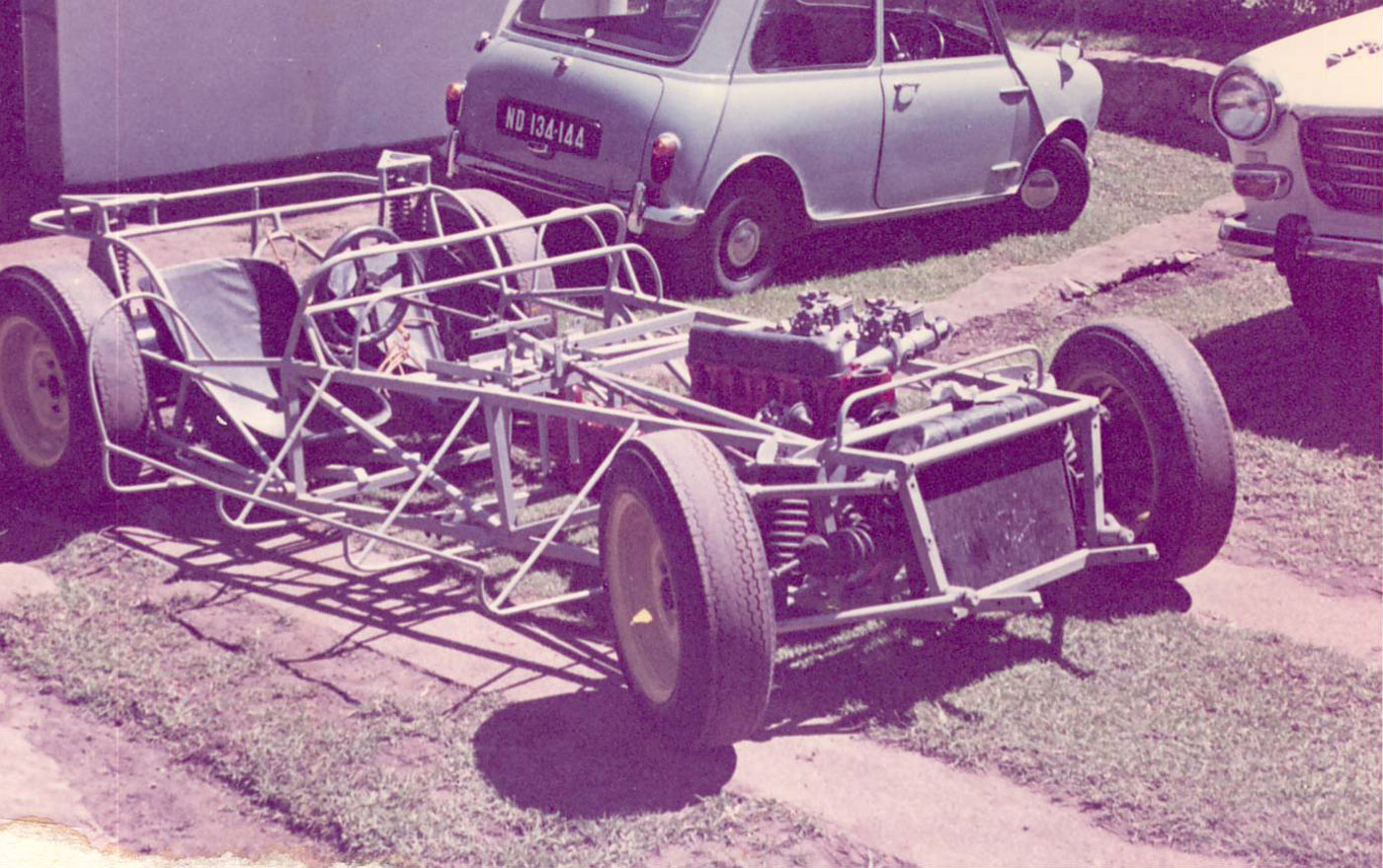

In this story, Syd Reinhardt shares his journey to his first Lotus, via an MG, and on to the Series 1 Elise he’s been driving since the first cars rolled off the boat into Australia.

Did Gordon Murray Improve on a Colin Chapman design?

Story and photos thanks to Syd Reinhardt.

My Lotus journey, a rather circuitous route, began with a question. Or two.

Was it real?

Had Gordon Murray actually built my car?

To quote the vendor, “Yes, Mr Murray has built it, himself. Fair dinkum. I swear”. His assurances rang true. I had a lot of fun with my Gordon Murray chassis, resulting in some excellent tales to tell, including the day I met the woman I was to marry many years later and the start of my Lotus journey.

It may seem contradictory, but my journey to Lotus began with an MG.

As a small boy in short pants clutching the hand of me Mum, I was entranced by an MG TC enthusiastically fanging around the corner of Adderley Street, the main street of Cape Town, roaring up into Strand Street and away. The tiny aeroscreens, the wonderful, classic sweeping line of the wings, the solid beam front axle canted over at a crazy angle, the lever arm shock absorbers completely overwhelmed, blue oil smoke pouring from the zorst. I’d never seen anything as exciting. I was captivated.

Later, I was to stand alongside one of these archetypal British sports cars gazing at the plethora of gauges, the 4 spoked steering wheel, the spindly spoked wheels and to know true love. An affection (affliction?) that has remained with me all my life. From the age of 19, I’ve never been without an early, wire wheeled MG. At one stage, I had 3 of them, one naturally aspirated, one supercharged and one a supercharged open wheel racing car.

At age 18, while traveling on the train, I saw a totally trashed TC lying neglected next to the tracks. I traced the owner and eventually bought it – $35 well spent – and then spent a year restoring it. I kept that car for around 50 years, eventually gifting it to my oldest son. It was, and is, a cracker of a car.

In my youth, my MG was my only car and my daily transport. I crammed my family – wife and 3 children – into it. My in-laws put intense pressure on me to “please buy a sensible car”. As if. My Afrikaans speaking mates nicknamed me “Spykerwiel”, Afrikaans for “Nail Wheels”. And of course, I had to race my MG. Or try to. It was all that I had, so it was pressed into service.

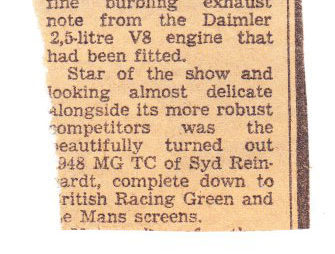

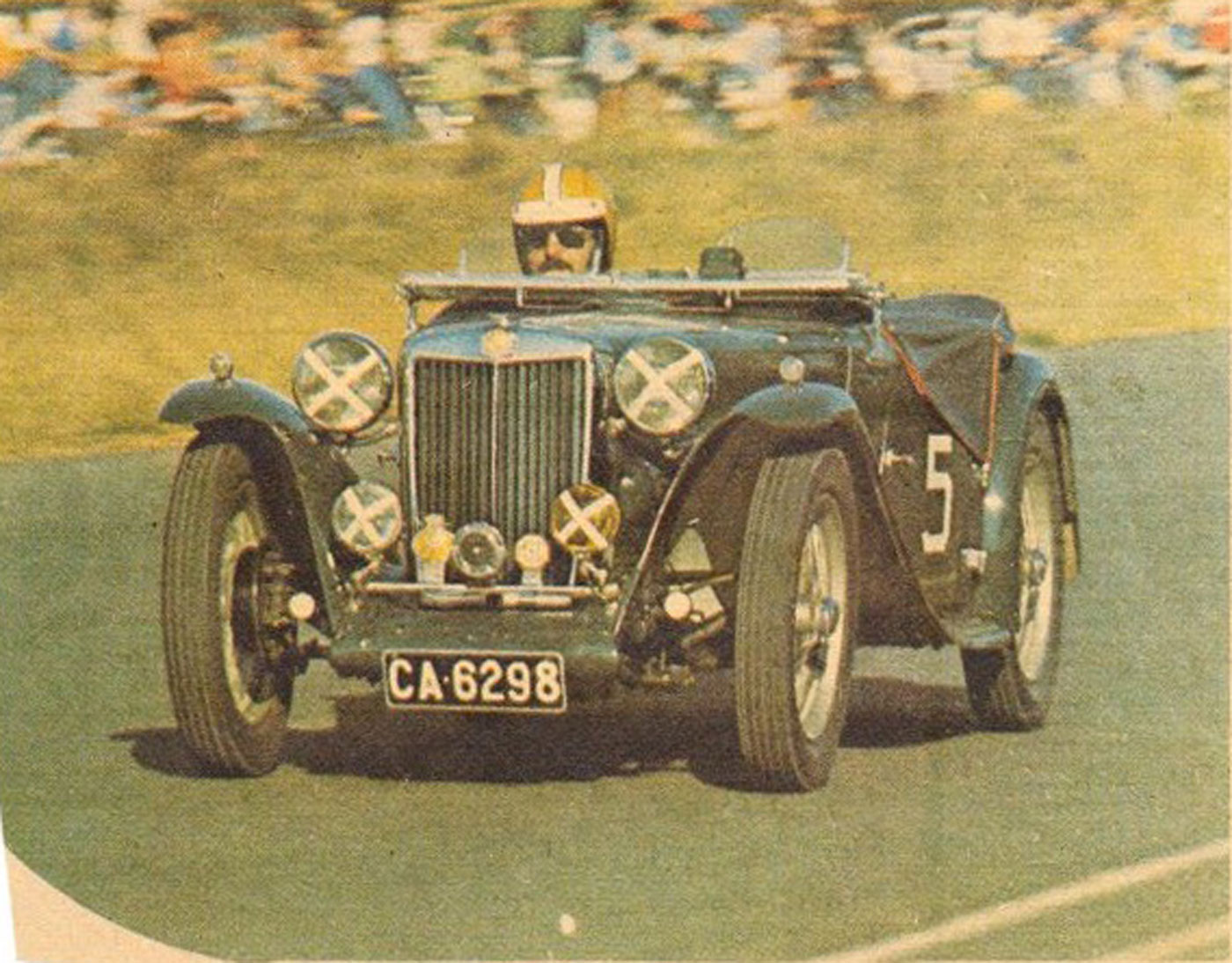

Above, at an early meeting at Roy Hesketh Circuit, near Durban. But not every meeting was quite as sympathetic, nor as successful. The competition was stiff.

Above, at an early meeting at Roy Hesketh Circuit, near Durban. But not every meeting was quite as sympathetic, nor as successful. The competition was stiff.

At race meetings, I would completely fill the large petrol tank, an upright reservoir hung at the very rear of the car. I’d use the weight at the rear and the minimal grip of those skinny tyres to fling the car sideways through the corners.

After each event, the rims would be filled with melted balls of rubber. I would be in the pits, frantically replacing the spokes that I’d just broken. Old guys would come up to me to shake my hand and tell me what a pleasure it was seeing the old car making such excellent sideways progress, “just like in the good old days”. (Nowadays, I’m one of the old guys myself).

Racing at Kyalami near Johannesburg. Where I was a mobile chicane.

With no seat belt and no roll bar and suicide doors that tended to open when the chassis twisted, the miracle is that I did not succeed in killing myself. But I digress. My MG, delightful as it was, was absolutely the wrong car for me to be competitive. It was time to upgrade. Time for a Lotus.

By this time I was living in the coastal city of Durban, one of the last outposts of British Colonialism in Africa. The name Lotus was whispered with great reverence. But who, living in the far-flung remote cities of Africa, could afford such a device?

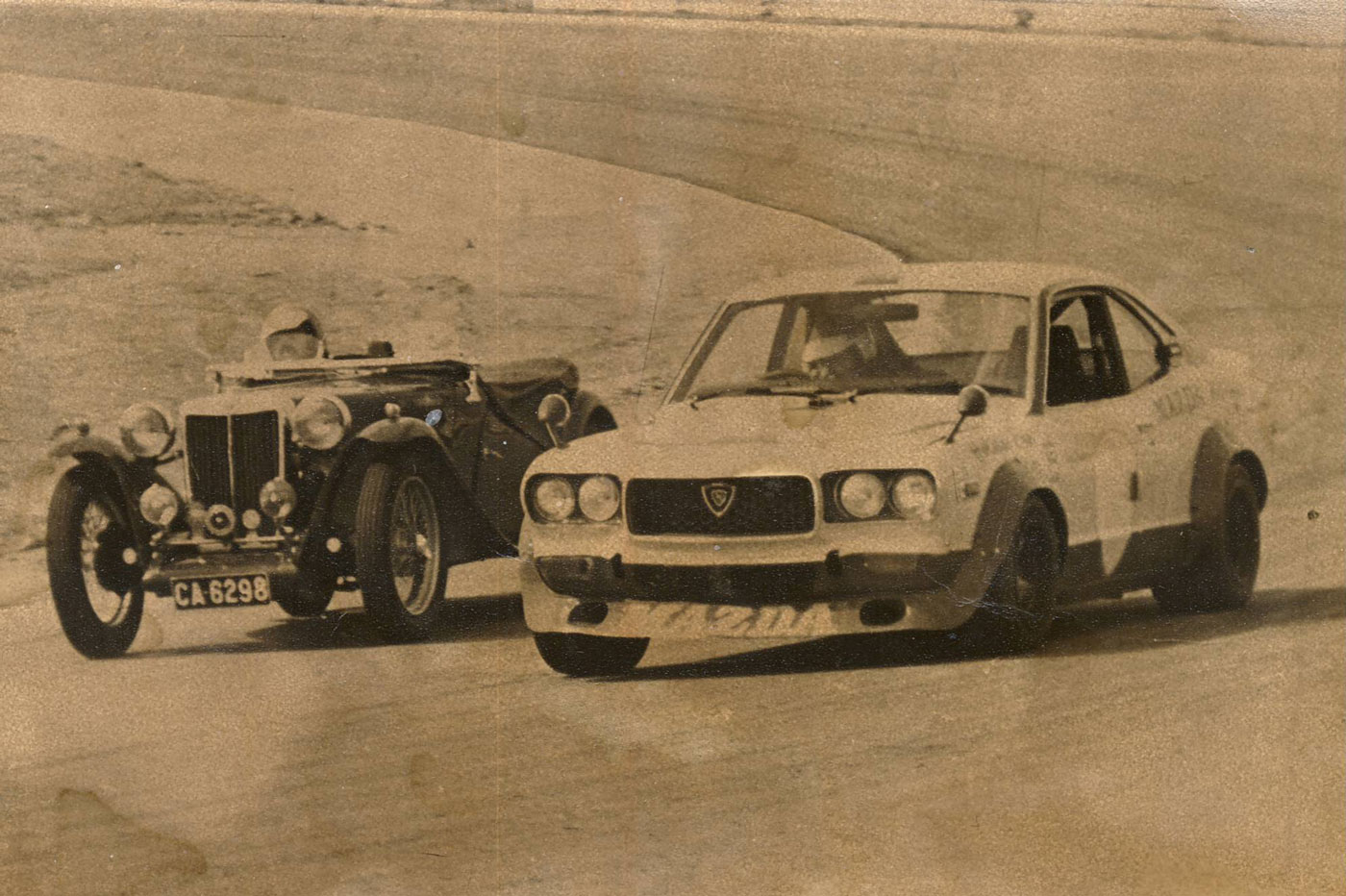

I learnt of a college student, an engineering maestro, who had already gone to England and was forging a formidable reputation with truly creative Formula 1 design. Before he left, he had built a number of replica Lotus 7 chassis. This was Gordon Murray, who had improved on the original design and sold a number of suitably-improved chassis to those who aspired to but could not afford or obtain a genuine Lotus. One of these chassis was as yet incomplete and was being offered at a very reasonable price.

A deal was done.

The vendor was in love with Lotus 11, had bought a Gordon Murray chassis and had welded outriggers to the chassis with a view to create a Lotus 11 lookalike. He had sourced a Ford 105e engine, all of 998cc, and assured me it was “full race and race ready”. Yeah, right. What that meant was that he’d skimmed an obscene amount off the cylinder head, sourced 2 twin choke webers, bolted a re-inforcing strap over the centre main bearing cap and that was it.

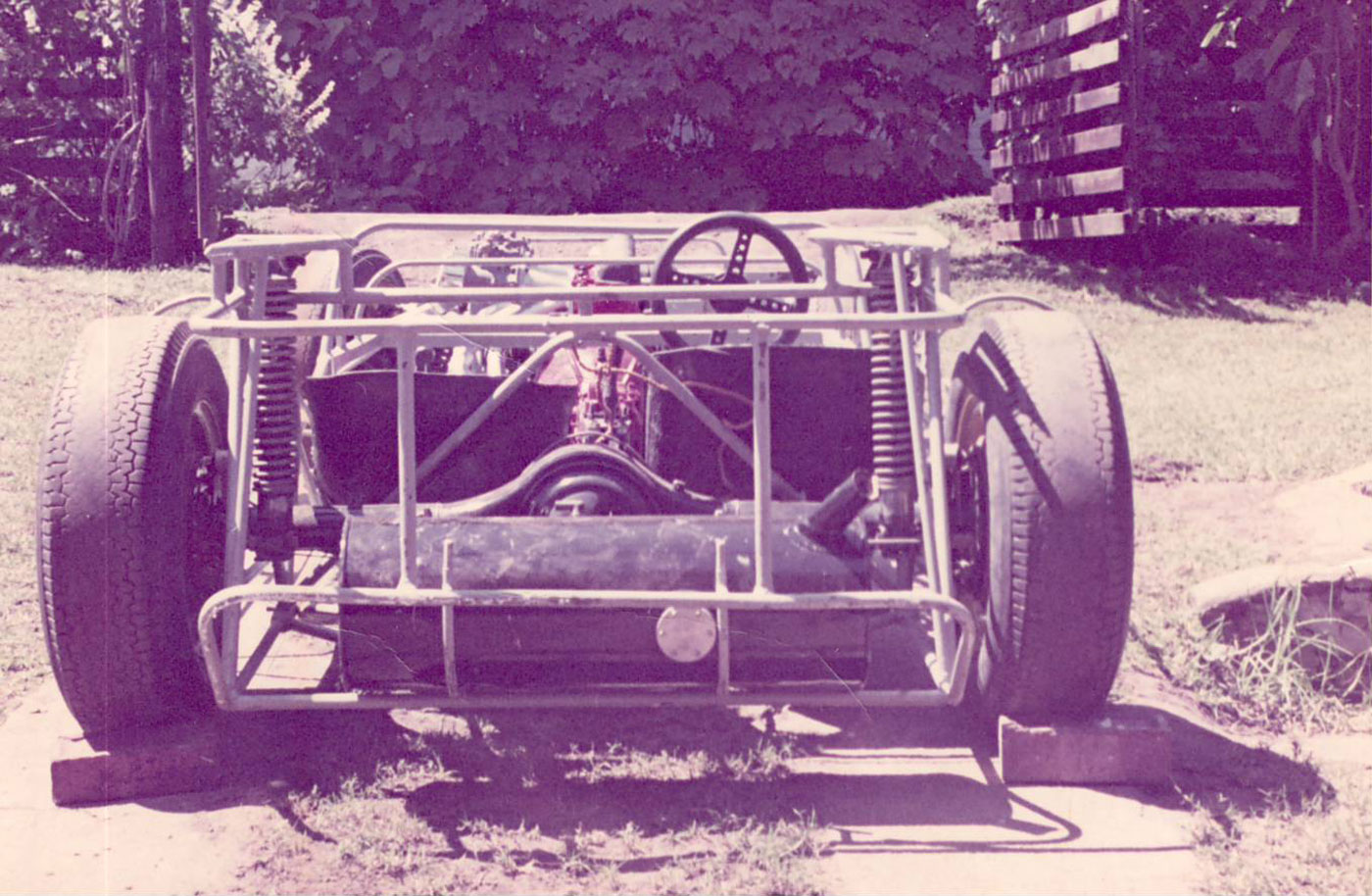

The tiny steering wheel had come off a disused printing press and there was zero bodywork, no floor, no electricals or gauges. No hydraulics. But in my starry eyed exuberance, it was magic. What was not to love?

I found some scrap aluminium, purchased an electric drill and a pop riveter, and on my shoestring budget, began to build my car. I was keen. My first competitive event was to be a hill climb up the escarpment from the coastal plain starting at the local sewage plant. Was location an omen?

I had an old repurposed very ragged lap belt from a scrapyard, had no roll cage, no bodywork, a patchwork of scrap aluminium pieces crudely pop riveted in place for the floor, a battery tied to the frame next to me with fencing wire, an open prop shaft spinning under my elbow, smooth tires that had almost no rubber left, so old that they should have been heritage listed, but hey, I was good to go.

Can you believe that the device in these photographs sailed through scrutineering? Those were the days!

Even though I was grappling with a recalcitrant engine that was in poor state of tune, nervous at my first serious competition and had never driven a hillclimb before, I could not fail to notice an extremely attractive spectator.

On my first ascent, the car became airborne and then, when it touched down, the impact proved too much for my pop riveting attempts. Half of the floor boards flew away. Random bits of aluminium flashed past me and I never saw them again. My feet were left hanging out in the open air. No one was bothered, least of all me.

Gradually my flying bedstead grew more panels, a more robust floor, a nose cone from a wrecked racing car, and I replaced the fencing wire over the battery with something rather more appropriate and less likely to cause a fire. It even sported a Lotus badge as a tribute to my bodywork attempts but the badge in reality was a credit to my imagination.

Eventually, I was to win the Natal Provincial Hillclimb Championship in my Lotus knock off. Now, to be fair, on the day there was a tussle for final honours and in the end a David and Goliath struggle ensued (for the record, I was David). My tiny 998cc Lotus-derived sports car was pitted against a fire breathing Goliath, a 7 litre very trick Camaro. The Cato Manor hill climb was not for the faint hearted, being exceedingly narrow, bumpy and twisty with no margin for error. In my tiny Lotus 7 knock off, the narrow and twisty bits worked in my favour, but what clinched the deal for me was my sump plug. Or rather, the lack of it.

After a day of competition, the Camaro and I were tied. It was to be a ‘sudden death’. On the final and deciding run, under stress because it was all or nothing at all, my exuberance was too great and I misjudged the final corner. I went wide and neatly and surgically severed the sump plug on an obstacle in the grass. This dumped the contents of the sump along the final stretch. In a cloud of smoke, I killed the engine and coasted over the line. When the big Camaro hit my oil, it was very impressive. Those were the good old days, no one cried “FOUL!” and so I took home the winners spoils.

Having succeeded with the challenges of hill climbing, I set my sights on something harder. I decided to try a race meeting. Lack of finance meant I could not afford a trailer, but this did not trouble me. I appropriated the company service ute and a length of ragged rope and coerced our workshop manager, a good mate, to tow me to the track. A measure of our friendship and also of my determination to compete is that the tow, using the ratty, knotted together rope, was 80km each way.

When I arrived in Australia more than 30 years ago, I was forcibly struck by how different public servants in Oz were to those I’d experienced in Africa. To my amazement, Australian officers in all works of officialdom seemed genuinely keen to assist me, to help me to overcome obstacles.

Africa had been so very, very different.

Public servants in South Africa seemed to be in place only to ensure that their job remained essential. And in order to be absolutely certain that they were irreplaceable, their attitude was to throw every possible obstacle in one’s path. Every by law, each regulation, would be scrutinised in order to try impede one’s efforts. The absolute worst of a terrible bunch were the local constabulary. And of those, woe betide anyone who crossed paths with the Highway Patrol.

Durban’s regional race track was Roy Hesketh, a rudimentary and challenging facility that was some 80km inland, near the little town of Pietermaritzburg. Today, it has gone the way of Oran Park and is a housing estate. The two cities of Durban and Pietermaritzburg are famous as they alternate each year as the start or end of the Comrades Marathon, an 80km ultra marathon run annually in opposite directions each year. The event attracts thousands of long-distance runners from all over the world. Skirting along the edge of the Valley of 1,000 Hills the scenic route undulates, twists and turns and gradually climbs the escarpment. Stunningly beautiful, this is the road we were happily driving on the way to the meeting, me sat at the end of my ragged rope in my wannabee racing car, my mate Steve in the company ute.

Half way to our race meeting, we were greeted by a siren, the police car hurtling past us and then aggressively signalling us to pull over. The traffic nazi strode over to me. Tall, blonde, militarily pressed khakis, wearing sunnies and a supercilious scowl. “And what” he grated “what do we have here?” Pause. “Hey???”

Knowing that I had to be very humble in the face of such magnificence, I begged forgiveness, explained that I was entered in the race meeting at Roy Hesketh Circuit near Pietermaritzburg and that we were on our way hence. “Ach, so!” grated the Nazi, “Well you are on a public road. Where is your official registration plate and insurance disc?” He already knew the answer. The guttural accent was thick enough to slice with a knife “Well if your veeehikkel is unregisterrrred, then the rubber may not even touch the public rrrroad!” I pleaded poverty, asked for sympathy and understanding. As if.

“I sympathise with youse. As a special koncession, I shall allow youse to turn around and go home and will not Konfiscate your veeehikkel.” He could not and would not be persuaded. My rubber was clearly upon the public road. The evidence was there for all to see. And that was that. Or nearly.

As we were about to turn around under his unrelenting gaze, I said “Sir, I cannot afford a trailer, what am I to do?” For which I got this amazingly good counsel. “Sonny, if you wish to tow this device, register it as a trailer for all I care, but it must be registered before its rubber may have any contact with the public road!”

He seemed to have a rubber and contact fetish. But who was I to argue? At least he did not penalise me for the sad and sorry state of my rubber.

Now, in those days, no one bothered too much about a trailer. After all, this was colonial Apartheid Africa. Roadworthy inspections for such a trivial device were unheard of. On Monday morning I presented myself at the local traffic registry, completed an official government buff yellow form and was presented with number plates and insurance discs for my ‘trailer’. These were indistinguishable from those issued with the registration of a motor car. I handed over the annual licence and insurance fee applicable for a trailer. 2 South African Rands, about a dollar! For that trivial amount, what I received was in every way identical to a full auto licence plate and disc, except for the tiny word “trailer” handwritten on the little disc where usually, the name of the manufacturer of the car would appear.

Suitably equipped with disc and plates I dispensed with the tow ute from that day on, and drove my “trailer” around for years. I paid the annual 2 Rand rego fee with great satisfaction. Would you not have done the same?

And what of the attractive spectator, she who I saw at my very first event, she who I was to marry many years later? To my gratitude and utter amazement, she had noticed me too.

Many years later she gave me a birthday present, a commemoration of when we first saw one another.

A Lotus. Another yellow one. A real one.

2 Comments on “A Circuitous Route: Syd Reinhardt’s Lotus Journey”

A great read ,thanks Syd.Most entertaining. Having spent a year in Capetown I can relate to the cop story.cheers Keith

A beautifully written and interesting story. Photos give it an extra lift.

Thanks for taking the trouble to write it.

Cheers

Richard